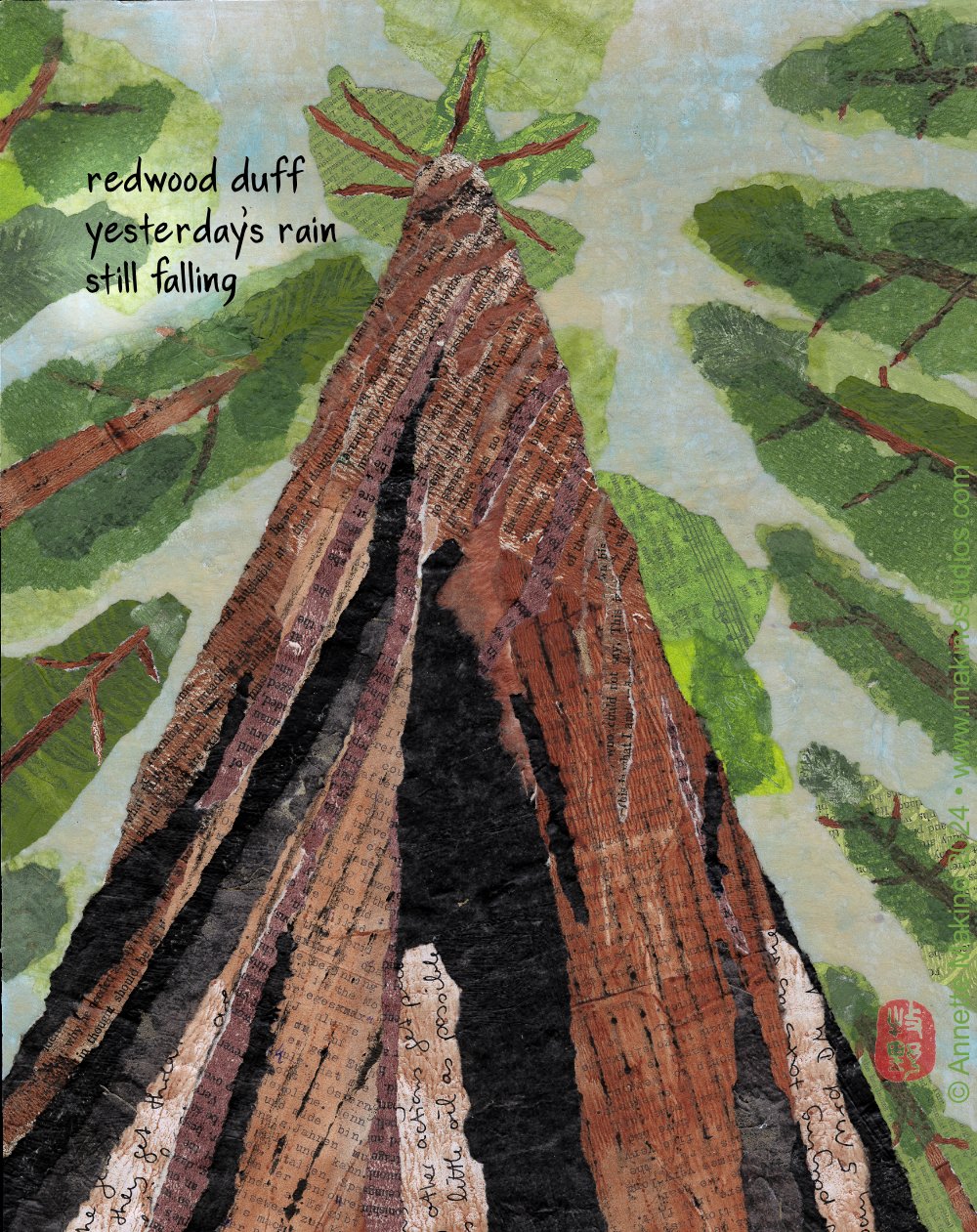

This image, “Redwood Duff,” by Annette Makino is a collage made from washi papers from Asia, old letters, book pages, music scores and gel prints of redwood tips, plus acrylic paint and glue on cradled wood.

Annette Makino first started making calendars as a teenager with her family; now she’s making calendars of her art and haiku that are sold the world over

HEATHER SHELTON, EUREKA TIMES-STANDARD, EUREKA, CA, SEPT. 29, 2024

Award-winning Arcata artist/poet Annette Makino has created mini-calendars of her art and haiku for 12 consecutive years. Her 2025 calendar is now available.

“Producing a calendar of my art is a deeply satisfying way to collect the best of the year’s work in one package that is then shared with the community,” Makino said. “When I turn to a new page, at the beginning of every month, I love knowing that hundreds of other people around the country and even overseas are doing the same that day.”

The 2025 calendar focuses on the landscapes, flora and fauna of Humboldt County, she said.

“Local folks will recognize our redwoods, oceans, dunes and barns, as well as an egret, field mouse, frog and migrating geese. A dog and a cat also make an appearance. Even a non-native creature, a sea turtle, is paired with a haiku I wrote here one frosty winter.”

Beginnings

Makino grew up with a Japanese father and a Swiss mother and lived in both Japan and Switzerland for short periods of time during her youth, though she was raised primarily in California.

Wherever she was, creativity was a cornerstone of her childhood, with she and her sisters Yuri and Yoshi regularly involved in projects like sewing quilts, making clay sculptures, tie-dying T-shirts, making batik wall hangings and more.

In 1976 when Makino was 13, her mom suggested her daughters work together to create a calendar adorned with their artwork.

“My mother, two younger sisters and I were living in Basel, Switzerland with my elderly grandmother that year,” Makino recalled. “One fall afternoon, my mom brought home a calendar for the following year with a blank space for each month’s image. She asked us three girls to create the art. We set to work with our colored markers on the floor of our shared bedroom. I remember drawing a scene of the birch woods near my grandmother’s house, fiery in yellow and orange leaves.

“The following January, we moved to a large commune/group house in a village an hour from Zurich, Switzerland,” she said. “My mom hung this first calendar in the main room of our private living area there.”

“The Poet’s Supper,” part of the 1985 Makino family calendar, is made with pen-and-ink plus colored pencil. © Annette Makino 1984

A year later, after they moved back to the United States, Makino and her sisters decided to create another calendar from scratch. They photocopied their work and gave the calendars to loved ones for the holidays, she said.

“The family and friends who received our calendars were so appreciative, it just became a tradition,” Makino said. “It was a rewarding way to showcase our work over the previous year and a fun group project for us three sisters.”

The trio continued the calendar-making tradition through their teens and college years.

“Now each calendar is a time capsule of our interests and abilities that year, as well as the trends of the times,” Makino said.

For instance, she says that in the 1970s, the sisters drew unicorns, butterflies, mimes and the like. The early ’80s, “gave way to punk/New Wave-inspired designs and absurdist pen and ink sketches,” she said.

“When we were in late high school and college, the calendars included portraits of boyfriends and, in the case of my sister, Yoshi, detailed assignments from art school,” Makino said. “Besides pen and ink drawings, we featured scratchboard art, black and white photos and linoleum block prints — anything that would Xerox well.”

As the sisters got busy in adulthood, it became harder for them to come up with four artworks each for the calendar, Makino said, and the three stopped producing their popular creations in 1987. Still, they each kept up with some form of art.

“We are a creative family,” Makino said. “My mother, Erika, took up sculpture in her 80s and produced clay or cement sculptures into her 90s, though at 96, she is mostly done with that. … My sister Yoshi teaches high school and middle school art. She also carves beautiful elemental designs into earth plaster and does all sorts of other creative projects. My sister Yuri is an independent filmmaker and film professor at the University of Arizona.”

Makino Studios

Artist/haiku poet Annette Makino is pictured in her studio. Makino has just released her 2025 mini-calendar, which features a colorful collection of her work. (Photo by Maya Makino)

Makino — who holds a degree in international relations from Stanford University and has years of experience as a communications specialist for nonprofit organizations — moved to Arcata in 1986 and opened Makino Studios — where she creates Japanese-inspired paintings and collages often combined with or inspired by her original haiku — in 2011. Her paintings are made using sumi ink and Japanese watercolors and her collages combine hand-painted and torn washi papers from Asia with found papers such as old maps and letters.

“I’ve always considered myself both a visual artist and a writer, and I’m fascinated by the interplay between words and images,” Makino said. “So, when I learned about the Japanese tradition of haiga, in which ink paintings are combined with haiku, I felt compelled to try it myself. In an effective haiga, the image and the poem move beyond illustration or description to enhance and deepen the whole. I find it a very rich and interesting art form.”

In addition to her original works, Makino sells greeting cards and prints, and also published an award-winning book of her haiku and haiga, “Water and Stone: Ten Years of Art and Haiku,” in 2021.

“I have a line of about 70 greeting cards,” Makino said. “Through trial and error, I’ve found that cards with haiku generally don’t sell that well. So for cards, I’ll use the same art but add different words that are more suited for sending for occasions like birthdays, holidays or condolences.”

And yes, she sells calendars, too.

In 2013, many years after those initial calendar-making projects with her sisters, Makino created the first calendar of her art and haiku.

“To my surprise, the 400 calendars I printed that year sold out,” said Makino, who notes she wasn’t “consciously thinking of our family calendar” when she decided to produce her first Makino Studios calendar.

“I just thought it would be a good experiment to see if people responded to a collection of my pieces in that form,” she said. “I only realized later that it was a sort of return to our family calendar tradition. And although my sisters don’t contribute art to this series, they provide really helpful feedback on the draft pieces, as does my artist daughter, Maya.”

And Makino says that while her artistic technique has improved since she was 13, “I still get just as much pleasure from creating a usable collection of art and sharing it with the world. In fact, I consider the Makino Studios mini-calendar to be a tiny rotating art gallery.”

This is the 12th annual calendar of art and haiku by Annette Makino.

She added, “At just $12 — the same price since 2014 — I think the calendar makes a nice holiday gift that brings a bit of joy and color to a small space, and maybe provides some food for thought. It has even inspired some recipients to start writing haiku.”

Makino’s work is sold mainly through local stores such as the Arcata and Eureka Co-ops and Eureka Natural Foods, and is also available through her website, https://www.makinostudios.com. She will have a Makino Studios booth at the “Holiday Craft Market” at the Arcata Community Center on Dec. 14 and 15 as well.